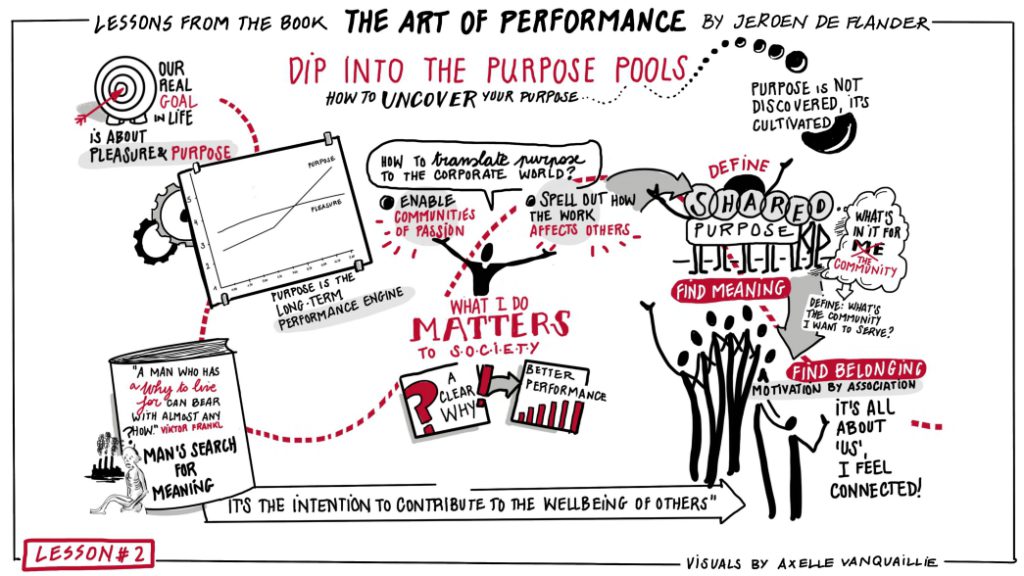

Finding purpose (at work) —the intention to contribute to the wellbeing of others—offers us psychological benefits, as well as a long-term performance boost.

Looking for meaning is part of being human. But as with passion, we don’t stumble upon our purpose. It requires an active approach to find an internal or external community we can serve and visualize the connection.

To boost performance, we have to mix passion (interest on steroids) and purpose. Interest is the sprint fibre, triggered by our human need for novelty and importance. Passion provides activation energy—the initial motivation. Purpose is the marathon muscle triggered by our human need to find meaning and belonging. Purpose makes performance last. It gives us a reason outside ourselves to keep going until the end.

Why in organizations

In May 2008, a group of leading business thinkers had a very ambitious goal: to define an agenda for management during the next 100 years. The so-called ‘renegade brigade’ led by Professor Gary Hamel, recently ranked by The Wall Street Journal as the world’s most influential business thinker, included academics such as C.K. Prahalad and Peter Senge, and progressive CEOs such as Whole Foods’ John Mackey.

What drew them together was a set of shared beliefs about the importance of management and a sense of urgency about reinventing it for a new era. For more than 100 years, advances in management—the structures, processes, and techniques—have helped to power economic progress. The problem however is that most of the fundamental breakthroughs in management occurred decades ago. The pace of innovation gradually decelerated and in recent years has slowed to a crawl. Management, like the combustion engine, is a mature technology that must now be reinvented for a new age.

With this in mind, the renegade brigade decided to lay out a roadmap for reinventing management.

The question they wanted to tackle: “What needs to be done to create organizations that are truly fit for the future?”

The reflection process resulted in a set of 25 ambitious goals that all leaders should strive for in the next 100 years to create Management 2.0. And at the top of that list, we find purpose and passion:

Ensure that the work of management serves a higher purpose. Most companies strive to maximize shareholder wealth—a goal that is inadequate in many respects. As an emotional catalyst, wealth maximization lacks the power to fully mobilize human energies. It’s an insufficient defense when people question the legitimacy of corporate power. And it’s not specific or compelling enough to spur renewal. For these reasons, tomorrow’s management practices must focus on the achievement of socially significant and noble goals.

Enable communities of passion. Passion is a significant multiplier of human accomplishment, particularly when like-minded individuals converge around a worthy cause. Yet a wealth of data indicates that most employees are emotionally disengaged at work. They are unfulfilled, and consequently their organizations underperform. Companies must encourage communities of passion by allowing individuals to find a higher calling within their work lives, by helping to connect employees who share similar passions, and by better aligning the organization’s objectives with the natural interests of its people.

Looking at the overwhelming evidence from scientific research and think tanks like the renegade brigade about the importance of passion and purpose on long-term performance, you would expect every company to focus on helping employees develop their interest and answer the why question.

Surprisingly, that doesn’t happen. It’s time we start to integrate the science of passion and purpose into the corporate world.

Purpose at work: a 3 step approach

The famous philosopher Aristotle was one of the first to point out that people look for at least 2 ways to find happiness—pleasure, which he called ‘hedonic’—and purpose, which he called ‘eudaimonic’.

More recently, when scientists at Johns Hopkins University conducted a poll of around 8,000 people and asked what they considered to be very important, 78 percent of all participants said that finding a purpose in life was their main goal. And similar surveys showed similar results. Besides satisfying our immediate needs—our pleasure—research shows that having a purpose in life is something we all long for. It’s a fundamental part of being human.

It’s deeply human to look for meaning in our lives. And it turns out that when we find our ‘why’, our long-term performance also improves drastically. Let’s take a look at some fascinating studies:

Tip #1: Searching for purpose has value in itself

Researchers Shoshana Dobrow and Daniel Heller recruited 450 amateur high school musicians. They wanted to find out if having a purpose would predict a different achievement in life. For the next 11 years, the musicians were followed and tested at regular intervals. Independent expert judges evaluated their skills level and purpose in life. Dobrow and Heller found that the students who scored high on the ‘why’ questions—those students who had a purpose—were able to become professional musicians regardless of their actual musical ability. As Heller points out, “our findings reveal an optimistic picture in which those with strong callings are more likely to take the risk, to persist, and ultimately succeed.”

Similarly, Ryan Duffy and his research colleagues followed medical students for a 2-year period to test the impact on life meaning. In line with the results from the high school musicians, students who were more advanced in their search for life meaning at the start of medical school were putting in more effort to get their degree. But intriguingly, even students who had not yet discovered their purpose but were actively looking had better performance results.

And that’s good news. We don’t need a final answer to our why question. Even putting in the effort of looking for meaning already has a positive impact on our performance!

Tip #2: Purpose requires a community

But how do we find our purpose? Is there a secret formula? Or do we just wait and hope we will bump into it?

Yale professor, Wrzesniewski, who studies purpose, points out that, “purpose is not discovered, it’s cultivated.” Like passion, purpose needs a deliberate effort to reach. So let’s learn how we can define our purpose. Let’s learn how we can dip into those purpose pools.

So in search of our purpose, the first question we have to answer is “what’s the community I want to serve?” To do so, let’s define purpose as simply as possible. Purpose is the intention to contribute to the wellbeing of others.

These others can be everyone on the planet (save the world), but mostly they are a much smaller group like our family, our friends, our neighbours, or co-workers. It’s our unique community. As a reader, for example, you are part of mine. Welcome! I sincerely hope my writing positively contributes to your life.

Tip #3 Belonging is the key driver

Next we ask ourselves, “How can I contribute to the wellbeing of my community?” This is where you connect your interest to your community.

They key purpose driver here turns out to be belonging—a social connection to another person or group.

And research from social psychologists Roy Baumeister and Timothy Leary shows that belonging is one of the most important human needs. Here’s how it works: belonging is an entryway to a social relationship—a small cue of social connection to another person or group in a performance domain. It functions as a psychological hub and facilitates diverse important outcomes—from motivation and achievement to health and wellbeing. So if you can make someone belong, everybody wins.

To give you a better feeling for the importance of belonging on the way we behave, take a closer look at this amazing experiment by Greg Walton and Geoffrey Cohen, 2 American psychologists.

A group of Yale undergraduates were invited to participate in a math experiment. At the start, the researchers announced they would all receive a complicated math puzzle. To prepare, they were asked to read a few short articles. One of these articles covered a story about former student Nathan Jackson. Jackson had gone to college not knowing what career to pursue and discovered he liked math. Today, he has a fine career in the math department at university. The one-pager also included Jackson’s biography including education, hometown, and birthday.

Now here’s the clever part: Jackson’s story was completely fictional, put together by the researchers. For half the participants, Jackson’s birthday was altered to match their own. For the other half, it was not. “We wanted to examine whether something as arbitrary as having a shared birthday would ignite a motivational response,” Walton comments. Furthermore, unknown to everyone except the researchers, the math puzzle was insolvable. Cohen and Walton wanted to test how long the students persisted.

When the results came in, even Cohen and Walton were surprised. In the ‘shared birthday’ group, the students’ motivation to perform exploded. They spend a whopping 65 percent more time trying to solve the impossible puzzle. And in a follow-up interview, they showed a more positive attitude towards math and greater belief in their own abilities. And all of this just by having a shared birthday.

What’s more, when asked, these students did not even register the birthday match consciously. “It got underneath them,” as Walton points out, “they were in a room by themselves taking the test. The door was shut; they were isolated; and yet [the birthday connection] had meaning for them. They were not alone. The love and interest in math became part of them. They have no idea why. Suddenly it was us doing this, not just me.” They belonged to a community.