The Pygmalion Effect (or Rosenthal effect) is a self fulfilling prophecy. The Pygmalion Effect – and counterpart Golem Effect – impact leadership performance.

The Pygmalion effect was first discovered in the classroom. Later, the Pygmalion effect in management was scientifically proven as well.

In fact, research shows that your success is a self-fulfilling prophecy!

Let’s take a closer look:

We all have great ideas.

And we often need the help of others to let them shine.

But geting the support from others is easier said than done.

We know—and have probably experienced firsthand—that people don’t always do what we like them to do.

We all struggle to get our ideas across.

And that’s because successful execution is much harder than many of us realize.

And failure doesn’t come so much because of the quality of the idea, but because of age-old, programmed human behavior.

It turns out that human nature kills big ideas.

Let’s take a look at the Pygmalion Effect (or Rosenthal effect)

The Pygmalion Effect / Rosenthal Effect: the ultimate guide

If you like, you can go directly to the following chapters:

- What is The Pygmalion Effect? (a cool video)

- The Pygmalion Effect: an example

- The Pygmalion Effect: definition

- The Golem Effect

What is The Pygmalion Effect?

Here’s a cool animation video made by Axellerator. It explains The Pygmalion Effect in a fun way and covers a definition and example.

The Pygmalion Effect: an example

Let’s take a closer look at the Pygmalion Effect in action.

The Pygmalion Effect was first discovered in the classroom by Robert Rosenthal, a Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Riverside and Lenore Jacobson.

But you find its effects everywhere.

We are going to study the Pygmalion Effect using a famous experiment in the army.

Dov Eden is a professor at the University of Tel Aviv. He studies belief. And his research reveals a remarkable trait of the impact of belief on performance

Consider a 15-week army course where 105 soldiers are assigned to one of 4 instructors. A few days before the start of the program, each instructor is briefed, including the following message:

We have compiled much data on the trainees including psychological test scores, sociometric evaluations, grades in previous courses, and ratings by previous commanders. Based on this information, we have predicted the command potential (CP) of each soldier. …Based on CP scores, we have designated each trainee as having either a high, regular or unknown CP, the latter due to incomplete records. When we’re not sure, we don’t guess. Soldiers of all 3 CP levels have been divided equally among the 4 training classes.

Each instructor was given their list of trainees (one-third of whom had a high CP, one-third a regular CP, and the remainder an unknown CP). They were then asked to copy each trainee’s command potential into their personal records and learn the names and scores before they arrived.

It’s important to know that, at the time, these 4 instructors didn’t know that the command potential classification—the performance score on the list they received—was completely random. In other words, the soldier listed as having the highest CP could very well be the worst soldier in the group.

After 16 weeks, at the end of the combat course, the performance of the 105 soldiers was tested in 4 different areas. One of these performance evaluations, for example, was their proficiency in the use of weapons they had been trained to master.

Pygmalion effect in the army: the outcome?

Those soldiers who got marked with a high command potential significantly outperformed their classmates in all 4 subjects. Those with an average CP scored the lowest. The third group—those with an unknown performance potential—ended up in the middle. The difference in performance between the best and the worst group was 15 percent.

After detailed analysis, it showed that the experimentally induced expectations—the fake command potential scores—explained al- most three-quarters of the variance in performance. In other words, by making a superior believe a subordinate has the ability to be a great performer, the actual performance increases. And the effect isn’t marginal. It’s a whopping 2-digit figure!

Strange, don’t you think?

When we believe a team member has the ability to be a great performer, our belief becomes reality. The performance expectation we have for our team members is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Pygmalion Effect definition

So what’s the secret?

How does the Pygmalion Effect work?

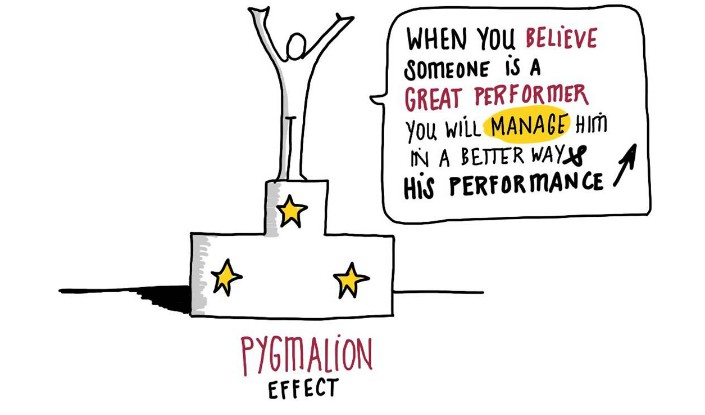

In short, the Pygmalion Effect or Rosenthal Effect is a leadership phenomenon.

As soon as the instructors believed that some soldiers had better abilities than others, they started managing those individuals differently. “Raising expectations triggers a leadership process that culminates in superior performance,” Eden points out.

In short: high expectations bring out the best leadership in a manager. Just imagine those instructors spending more time with ‘promising’ soldiers, highlighting successes, showing best practices, and teaching them how to deal with stressful situations. Better leadership, in turn, has a direct, positive effect on the subordinate’s performance. It kick-starts positive effects. Just imagine the extra boost the belief system from the ‘promising’ soldiers gets by the extra positive attention from their instructor.

The Golem Effect

But the Pygmalion Effect has an evil twin brother called the Golem Effect. While positive expectations from the leader fuel the self-fulfilling prophecy, negatives ones create a downward spiral that leads to lower performance.

The Golem Effect, an example

What is the opposite of the Pygmalion Effect?

Take the following true story that happened in a factory assembling disposable sterile medical kits for use in blood transfusion.

Its plant manager, who had heard a lecture about the Golem Effect, was having a problem with the productivity of new workers. They were either native or Eastern European immigrants. And everyone at the plant ‘knew’ that the natives were poor workers in comparison to the immigrants. They adjusted slower, took longer to reach standard production, and had difficulty maintaining it. In particular, the head supervisor, who had been responsible for putting new hires to work for years, ‘knew’ the native women would give her trouble.

The plant manager however believed the native workers to be as capable as the immigrants. As he suspected that the head supervisor had a negative prejudice towards the native’s performance, he told her that he had personally handpicked the native new hires that were to start the following week. He also told her they were excellent people, expected to reach standard production targets quickly. As usual, the head supervisor promised to report any problems to him.

But surprisingly, this time, there weren’t any. In fact, it was the smoothest intake of new hires that anyone in the plant could remember. The new native recruits achieved the standard in record time and, soon after, some even outperformed the norm. The supervisor complemented the plant manager for improving his hiring decisions.

Isn’t that amazing?

Just by raising the expectations in the supervisor’s mind, the native group performed outstandingly. The recruits weren’t handpicked, but by making the supervisor think they were, her performance expectations of the new recruits changed from negative to positive. Eden argues that when we expect low performance, we get low performance.

It’s a negative self-fulfilling prophecy—the Golem Effect. It’s the opposite of the Pygmalion Effect.

By changing expectations, we can change the outcome. The negative spiral triggered by negative performance expectations (they can’t) becomes a positive one (they can). The result? Better performance.

Golem and Pygmalion: another example

A few years ago, I was fortunate to be involved in a project to see both Pygmalion and Golem at work.

A large financial institution wanted to fire about 100 employees that had been identified as low performers by their boss. Over a number of years, this group of low performers consistently received a low score on their performance evaluation. According to their superior, they didn’t add any value. To comply with the law, senior leadership involved the worker’s union. They agreed to the course of action but challenged the quality of the performance rating. A compromise was found. Over a one-year period, the low performers were individually coached by an independent coach using a positive approach. They weren’t treated as low performers anymore. At the end of the year, their performance was evaluated again. If it didn’t meet company standards, they got fired as initially planned. But if their performance improved, they got to stay and the ‘low performer’ stigma was definitely removed.

A year later, to the surprise of many, a little over half of the group performed on, or even above standard. When we took a closer look, we found clear evidence that those who relaunched themselves had troubled relationships with their boss. There was a lack of belief in their ability to succeed, as we saw with the native workers.

The Pygmalion effect & Golem effect: what should we remember?

“Leaders get the performance they expect,” Eden argues.

When we expect low performance, our expectations kick-start a negative spiral that leads to low performance. “Underachievers grow accustomed to getting by with minimally acceptable performance simply because nothing more is expected of them.”

Just by replacing a management style of negative comments and neglect with a ‘can do’ approach, it was possible to turn the negative spiral into a positive one for over 50 percent. And this was a group previously identified as chronic low performers.

Imagine the power of Pygmalion if we apply a ‘can do’ management style to everyone in the team.

Both the Pygmalion and Golem Effect are important for us. When we believe our team members have what it takes to succeed —like the 4 instructors did with those high CP soldiers—the chance they actually will increases significantly. Higher expectations lead to better performance. But when we expect our fellow travelers to fail—like the supervisor expected from native workers—they probably will.

What do we learn about the pygmalion effect?

Eden and Co teach us that we have to be careful in what we believe. Most of us have the habit of labeling team members. Maria is a high performer, Joe is average, Eva reached her ceiling, and Mike is a low performer.

But our labels are self-fulfilling prophecies.

And for those that end up in the high performance category, that’s great. They’ll get the leader they deserve. But for those that we categorize as average or low performers, it’s not. Because when we don’t expect greatness, our leadership won’t be great either. And by doing so, we contribute to their failure.

If we want to increase strategy success, we have to reconsider the relationship we have with all our team members.

We need to cultivate a ‘can do’ environment, a place where we expect success from every team member, not only a few high performers. Army instructors who believe all soldiers will succeed have better combat troops than those who don’t. Factory supervisors who believe all workers will succeed produce more than those who don’t. Leaders who believe all travelers will succeed outperform those who don’t.

Beyond Pygmalion & Golem

In the end, to succeed as a strategist, we need a thorough understanding of what makes people tick. And that’s on top of industry dynamics, customer behaviors and financial savyiness.

We need to have a deep understanding of how people process information and take decisions, what makes them care about an idea, and what gives them the energy to take action. And when we do, our idea has all it needs to succeed.

Like this article about the Pygmalion Effect/ Rosenthal Effect psychology & Golem?

Want to inspire others?

Share now!